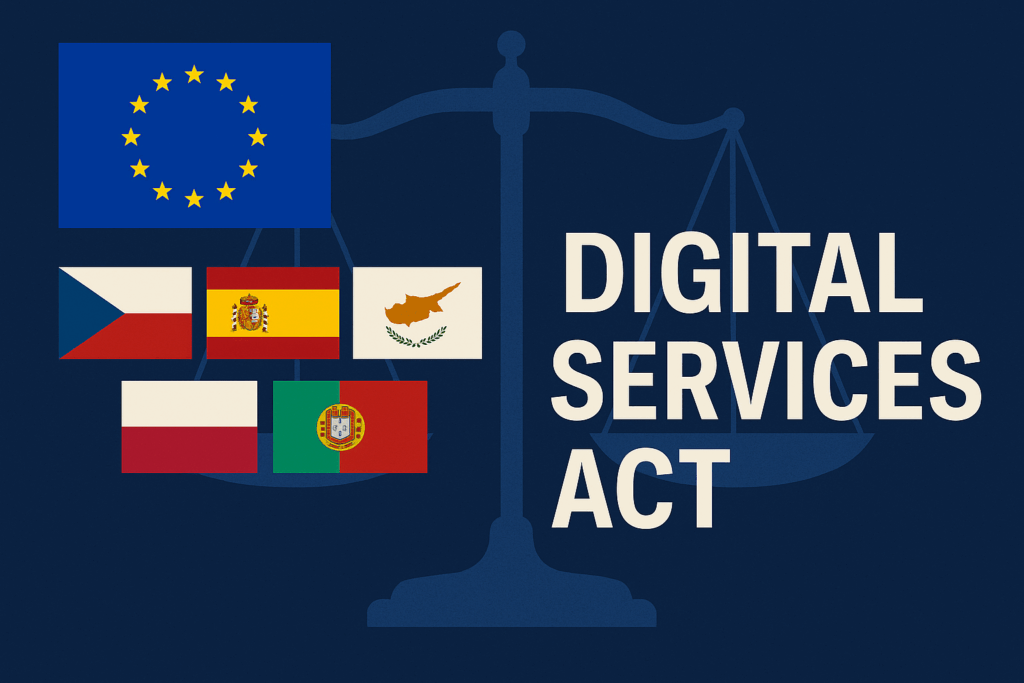

On 7 May 2025, the European Commission took the significant step of referring five Member States—Czechia, Spain, Cyprus, Poland and Portugal—to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) for failing to transpose key provisions of the Digital Services Act (DSA) into national law. This development underscores the Commission’s determination to ensure uniform application of the DSA across the Single Market, and it carries important implications for digital service providers, national regulators and legal practitioners alike.

Background: The Digital Services Act and National Coordinators

The DSA (Regulation 2022/2065) represents one of the flagship pieces of EU digital legislation, aiming to modernise the legal framework for online platforms, enhance user safety, and foster transparency in content moderation. A cornerstone of the DSA is the creation of a network of Digital Services Coordinators (DSCs)—one in each Member State—responsible for supervising and enforcing the Regulation’s requirements at the national level.

Under Article 49 of the DSA, each Member State was required to:

- Designate a DSC by 17 February 2024;

- Empower that DSC with the necessary investigatory and enforcement powers;

- Establish effective and dissuasive rules for penalties for infringements of the Regulation.

The DSC network works in close cooperation with the Commission and other national authorities to ensure a harmonised enforcement regime, covering obligations such as risk assessments by very large platforms, requirements for notice-and-action mechanisms, and the transparency of advertising.

The Referral: Failures to Designate, Empower and Penalise

Despite the clear deadlines, the Commission’s press release confirms that:

- Poland failed entirely to designate and empower a DSC by the stipulated date.

- Czechia, Spain, Cyprus and Portugal each designated a DSC, but have not conferred upon it the full panoply of powers necessary for effective supervision—such as access to information, investigative authority, and sanctioning capability.

- None of the five Member States has yet laid down rules on penalties for DSA infringements, leaving a critical enforcement gap.

As a result, the Commission has initiated infringement procedures that now progress to referral before the CJEU, the final arbiter in ensuring compliance with EU law.

Significance for Digital Service Providers and Regulators

- Legal Certainty and Compliance Pressure

For tech companies operating in these jurisdictions, the referral signals heightened legal risk. Without empowered national authorities, service providers lack clarity on enforcement expectations. Post-CJEU ruling, swift implementation may follow, triggering immediate compliance obligations and potential fines. - Enforcement Uniformity

The DSA’s success hinges on uniform application. Disparate enforcement regimes—or worse, regulatory vacuums—undermine the single digital market and may incentivise “forum shopping” by platforms seeking lax jurisdictions. The Commission’s action thus serves as a reminder that divergence will not be tolerated. - Precedent for Future Legislation

The referral illustrates the EU’s willingness to litigate over digital policy transposition. As the Digital Markets Act (DMA) and forthcoming AI Act take shape, Member States should anticipate similar scrutiny of transposition timelines and substantive enforcement frameworks.

An administrative challenge or an intentionally delayed or diluted DSA enforcement?

An educated conjecture arises: could Czechia, Spain, Cyprus, Poland and Portugal have intentionally delayed or diluted DSA enforcement to position themselves as more “business-friendly” destinations for technology investment? Several factors support this hypothesis:

- Economic Incentives: All five countries have been actively courting foreign direct investment in their digital sectors. A less stringent regulatory environment might seem attractive to start-ups and established platforms alike.

- Regulatory Competitiveness: Amid global competition for data centres, R&D facilities and cloud infrastructure, Member States may perceive a relaxed enforcement landscape as a competitive edge.

Conversely, the delays may simply reflect resource constraints or political priorities, rather than a deliberate strategy. The lack of designated sanctioning regimes and empowered DSCs could stem from bureaucratic inertia rather than a calculated policy to under-regulate.

While definitive motives and circumstances remain opaque, legal practitioners should monitor ensuing CJEU judgements closely. A finding of deliberate non-compliance could invite not only mandated corrections but also reputational repercussions and heightened post-transposition scrutiny.

Conclusion

The Commission’s decision to refer five Member States to the CJEU over DSA transposition marks an important moment in EU digital governance. For legal advisors, compliance officers and platform operators, it underscores the need for vigilance regarding national enforcement landscapes. Equally, it raises broader questions about the balance between attracting digital investment and upholding the rule of EU law. As the infringement procedures unfold, stakeholders will be watching to see whether the CJEU’s eventual rulings result in a more consistent and robust enforcement regime—or whether the Member States in question will redouble efforts to signal a pro-tech, light-regulation stance.